A recent toot on Mastodon reminded me of a phenomenon I believe is pretty common these days: An unusual event causes us to reconsider our habits and assumptions in some way.

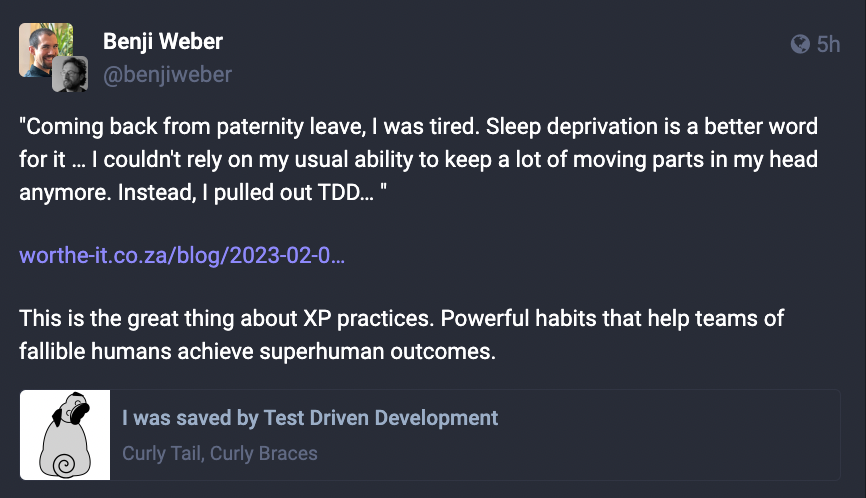

The toot was this one from Benji Weber, posted on February 9, 2023:

The blog post he references is here: I Was Saved By Test Driven Development.

The toot and blog post explain what happened clearly enough; there’s no need to reiterate the details.

The angle I’d like to bring out is the pattern: We operate in domain X in a certain way based on our established habits and our assumptions about the best way to do X. Then something unexpected and/or unusual happens that causes our habitual way of doing X to be uncomfortable, clumsy, expensive, or unworkable. At that point we reconsider our habits and assumptions, and possibly change the way we do X.

In Benji’s story, the sleep deprivation he experienced during paternity leave followed him back to the office. He struggled to get work done using his habitual approach of keeping a lot of moving parts in his head. In a way, he was forced out of his comfort zone, and he sought a different way of working that would help him get things done.

His blog post describes test-driven development (TDD) as if it were something brand new that requires an explanation. As a long-time practitioner, that struck me as odd at first. There’s nothing new about TDD, and there’s no question of its value in our line of work.

Why is Benji late to the party in this regard? Because of longstanding habits and assumptions. His previous way of working served him well enough. When our current habits and assumptions aren’t causing us any grief, we don’t have a reason to pause and ask ourselves, “Hey, self! Why are we doing X in this particular way? Is there a better way?” Why would we do that, after all? We’re already busy, and nothing seems to be wrong anyway.

So, why am I suddenly rambling on about this so-called “pattern?” There’s a piece of conventional wisdom that says we tend to see whatever we’re looking for. We might not notice something that’s right under our noses if we aren’t aware of its existence, or if our habit is to focus on some other thing that’s also right under our noses. Once I perceived the pattern in several events of larger scope than software development, I started to notice it in other areas, as well. Now it’s hard for me to “unsee” it.

The Decline of Twitter

Twitter is a social media platform. The purpose of social media is to enable social interaction among friends, acquaintences, colleagues, and people who share an interest. But that is not the only reason we use the Internet. Most of us consume content of various kinds, from news to entertainment, or depend on the Internet as a kind of global library or encyclopedia. I learned how to install a ceiling fan from a video on YouTube, for example. We depend on the Internet for house-hunting when we need to relocate.

We learn new skills, read about history, study foreign languages, play games, follow our favorite sports teams and musical performers, monitor political developments, support social justice causes, raise funds for projects, discover information about things we didn’t know about, and do many other things besides interacting socially with our friends. Many of us create content we want to share or publish in some form. We also depend on the Internet for business and professional connections, and to find opportunities for work.

Each of these activities – call them “use cases,” if you will – is different and is supported by different online facilities and resources. Only a few of them amount to “social interaction.”

Like many others, I had gotten into the habit of using Twitter for every use case I have for the Internet. Relatively little of that involves social interaction. Yet, I channeled every online activity through Twitter.

Twitter is designed and operated in a way intended to lock our eyeballs in place. Until it became untenable, it was a difficult habit to break. Although I was aware that I was wasting a lot of time looking at Twitter, I didn’t pause to question the habit until the new owner wrecked the user experience altogether. Alongside many others, I looked for another place to “park” online.

In the process, I asked myself what I actually used Twitter for. I came up with a list of quite a few things, only one of which was social interaction. I realized that business contacts belong elsewhere – possibly on an interactive facility, but not on a social media platform as such. Twitter had become a haven for hate speech, and was no longer useful for social interaction.

And it was absolutely unnecessary for any other Internet use case. All the photos, videos, and articles people linked in their Tweets are already available elsewhere on the Internet, without exception. All the opportunities to make business contacts and promote ourselves professionally already exist elsewhere on the Internet, without exception.

But to shake us out of our comfort zone, an unusual event was required.

My guess is that millions of people were forced to pause and reconsider their Twitter habit after October 28, 2022.

Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the world made a faulty assumption – that Russia was ready to join the community of nations – and got into an unhealthy habit – engaging with Russia as if it were a member of the community of nations.

But Russia is still the same Russia it has been for the past 1,100 years. We have had ample time to observe their behavior and understand what they are. They reminded everyone of this when they invaded Ukraine in 2022. Some 40 million people in northern Africa and the Middle East went hungry when grain shipments from Ukraine and western Russia ceased. Europe suffered winter fuel shortages and crippling fuel costs. China worried that Russia might exhaust itself in the war and be unable to meet its contractual obligations to supply raw materials to the Chinese industrial machine.

And after Medvedev’s public statement that they wanted to see a Russian-controlled “zone” stretching from Lisbon, Portugal, to the Pacific Ocean, Russia’s neighbors began to worry they might be next in line after Ukraine, either for conquest (Finland, Sweden, etc.) or as a source of cannon fodder and resources without the option to say “no” (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, etc.).

As a result, people’s assumptions about Russia have changed. Rather than assuming Russia is “just another country,” other governments now understand Russia must be contained. And people’s habits about interacting with Russia have changed. European countries are rapidly moving away from dependency on Russia for oil and gas – even if that means re-instituting coal and nuclear facilities in the short term. African countries are starting agricultural programs to establish independence in food production. They are also expanding trade to include more food-exporting countries as a way to spread their risk – Uruguay, Vietnam, Thailand, etc.

Cooperation with Russia in scientific ventures by countries like the US, Japan, Australia, and South Korea are now closely monitored and controlled. Countries that desire good relations with Russia – notably China and India – are increasing diplomatic activity with Russia; not because they approve of the atrocities in Ukraine, but as a way to prevent the situation from spinning out of control. A large-scale war would not serve their interests. They recognize that even if their goals are aligned with Russia’s from time to time, Russia will never be a reliable ally or “friend” in any sense.

The reason this is an example of the pattern is that nothing about Russia has actually changed. The day before the invasion they were exactly the same Russia as they are today. The invasion caused the rest of us to pause and reconsider our assumptions and habits about Russia.

But there is really nothing “new” here – in the same way that Twitter was already not the best or only way to use the Internet, and keeping a lot of moving parts in your head was already not the best or only way to develop and support software, Russia was already Russia.

The Pandemic Lockdown

The Coronavirus pandemic had a wide range of damaging effects on the world. One of those has been a sea change in the way most Western people perceive their relationship with their employers.

Even white-collar workers and professionals have long been treated, in effect, as wage slaves by large corporations. The game has been to keep us living at a financial level that was just sufficient for a reasonable degree of material comfort, but not so secure that we would feel confident enough to walk away from a negative work experience. They wanted us to remain just one or two paychecks away from living on the street.

Blue-collar workers had it worse. Employers restricted their hours to a level below the government-mandated minimum for benefits, forcing people to work multiple jobs with no benefits in order to make ends meet.

It was Brave New World as opposed to 1984. Mass entertainment media were our soma.

Today, corporations have started to complain about the fact many white-collar workers don’t want to return to the status quo ante. They prefer working remotely whenever it makes sense. Many jobs really don’t have to be done in an office, thanks to the Internet. People also resist traditional full-time employment, preferring a “gig” style of engagement with the job market. It gives individuals more control over their own time and lives. And that’s the last thing big corporations want people to have.

Similarly, skilled blue-collar workers have taken charge of their own time. They pick and choose clients and assignments, set their own prices, and take time off when they want to. They sign work agreements directly with the end customers of their skilled services, rather than working on an hourly basis for a service company that rakes in all the profit and keeps the workers worried about layoffs.

The only segment of the workforce that is still at a disadvantage are unskilled blue-collar workers. In a society that doesn’t value people for their own sake, like that of the United States, they will always face challenges because they have no marketable skills; they are just muscle.

These societal changes reflect the same pattern – an unusual event caused people to pause and reconsider their assumptions and habits regarding work and employment.

There’s nothing “new” here. The old way of working was already not optimal for workers.

The Global Supply Chain

Possibly the largest-scale example of the pattern is the disruption of the global supply chain due to the pandemic lockdowns.

Just prior to the start of the pandemic, the entire world was organized more-or-less as a single factory. There was one supply chain worldwide. It was optimized for efficiency, low cost, and just-in-time delivery at each stage.

What enabled such a system in the first place? It was a program of international cooperation dictated by the United States in the 1940s at a large meeting of international representatives at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. The US was emerging as the sole growth-generating economic engine in the world – the only major economic power still standing at the end of World War II.

The US did two things nobody expected. First, they offered to purchase whatever other countries could manage to produce, as a way of helping them restart their national economies. Second, they took on the responsibility of protecting global shipping lanes, using the US Navy to suppress piracy – without regard to whether the ships they protected belonged to a friendly or unfriendly country.

No one was in a position to force the US to do these things. The US could have dictated any terms it wished at the end of the war. No one else had the resources or the will to fight any longer. That’s why it surprised so many people. Instead of taking advantage of the relative weakness of other countries, they helped rebuild – including their World War II adversaries. And they did it in a way that made war unnecessary for countries to access the resources they needed to run their economies.

The Bretton Woods system allowed countries to cooperate instead of competing for access to resources and markets. And cooperate they did. With the US Navy standing guard over shipping, the international community created a single global supply chain that operated on a just-in-time basis.

It worked well – provided nothing ever went wrong. That proved to be a major caveat. Everyone’s national economies were optimized for low cost and efficiency, and not for resiliency.

We got a taste of the fragility of the system when the container ship Ever Given became lodged in the Suez Canal. (Here’s a BBC report about the incident.) The blockage stalled about 12% of global shipping for a time.

The Suez Canal blockage wasn’t enough to cause international decision-makers to question their assumptions or change their habits; but the combined effects of the economic slowdown due to pandemic lockdowns and the interruption of food and fuel shipments due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine were enough.

Individual countries have been working to make themselves more independent and make their economies more resilient. The United States, for its part, no longer gains much value from the Bretton Woods system, and additionally it seems to be coming apart at the seams from within as Americans turn against each other in a way that appears irreversible and irreconcilable. Lacking a sense of unity, Americans will have no shared concept of national vested interest, and therefore will not support the cost of protecting global shipping.

Should the US be called upon to defend Taiwan against China, it will do so and it will prevail, but only at high cost. The most optimistic simulations have the US losing hundreds of ships and aircraft and thousands of hard-to-replace personnel, such as jet pilots. It may no longer have sufficient naval power to patrol the world’s shipping lanes, even if doing so were still in its interest.

The emerging world order requires different habits in the area of international trade. Costs will be higher as each country has to defend its own ships, as was always the case prior to Bretton Woods. Countries that seem to be peaceful just now may be at war once again, trying to gain access to each other’s resources, when no one guarantees such access. Each country must find ways to feed its own people – the assumption that they can rely on imports must change.

These changes in habits and assumptions are of much larger scope than the changes Benji writes about in his blog post, but they are an example of exactly the same pattern – an unexpected event forces people to reconsider their habits and assumptions. And just as with the previous examples, there’s nothing really “new” here – it was already a bad idea to build an international economic system that lacked resiliency.

Of Cockroaches and Kings

Today’s world faces a number of problems. The most serious of these is climate change. Recent information about the effects suggests the speed of climate change is increasing. Earlier estimates gave us a few decades to reverse or stabilize the changes, but now it seems as if significant effects will occur within a single decade, and nothing humans are capable of doing can stop them, even if we tried. And we aren’t trying.

Even so, decision-makers in leading governments and corporations continue to behave the same way as they did a century ago. They seem oblivious to the danger.

Are they really oblivious, or are they simply following established habits based on conventional assumptions? What sort of event might shake them out of their comfort zone?

I’m reminded of something that happened in our kitchen when I was a child. We were poor, and lived in low-income housing. A common feature of low-income housing is that the buildings are infested with cockroaches. Whenever we entered the kitchen at night and switched on the light, cockroaches scurried away as quickly as they could.

For some time, we were unable to locate their nest. One day, I picked up the small electric clock we kept on the kitchen counter. Beneath it was a clump of cockroaches. They established their base of operations under the clock, possibly because it was warm and vibrated slightly.

We were able to eliminate the nest entirely, with ease. The animals did not run away. They just stood there, waving their antennae. They were already in their safe haven. They had no idea what to do differently, once the clock was moved. The fact it was a matter of life or death for them didn’t matter. They were unable to change their habits.

So they died.

I have to wonder if the big decision-makers of the world are clustered together in their traditional mental safe haven, unable to change their habits even when they can smell the cold, stale breath of Death in their faces.

Conclusion

So, yeah, it’s cool that Benji has discovered TDD. It’s a pretty useful approach to software development.