There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, "Morning, boys, how’s the water?" And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, "What the hell is water?"

None of this is about morality, or religion, or dogma, or big fancy questions of life after death. The capital-T Truth is about life before death. It is about making it to 30, or maybe 50, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head. It is about simple awareness—awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, that we have to keep reminding ourselves, over and over: "This is water, this is water."

(David Foster Wallace, commencement speech at Kenyon College, Ohio).

Yeah, so if you care to Google it, you’ll find lots of articles pondering the reasons why the majority of Lean, Six Sigma, Agile, Kaizen, TQM, and name-your-poison adoptions "fail." People you and I know from conferences and books and such tell the same stories over and over again of the one big success they had with organizational transformation. Everyone was stoked about their branded re-packaging of old ideas made new again through the magic of buzzwords. They achieved improvements of 4x, 10x, 50x, or more X’s than you’d care to count. One or two years after the consultants left the building, those organizations were back where they started. I’ve seen it happen myself. The organizations snapped back to their old equilibrium state. Maybe they always do. The buzzwords haunt the place like fading poltergeists, and the stories live on, but the substance is long gone.

If you’ve done much Value Stream Mapping in information-shuffling organizations (as opposed to thing-making organizations), then you’ve probably done a double-take a few times, unable to believe process cycle efficiency could really be as low as that, and the company doesn’t sink through the earth’s crust like the superdense slug it is. It seems they’re happy as can be to spend 3 or 4 million dollars and burn up a year of 75 people’s precious time to build a routine, web-based CRUD app, fundamentally no different from a million others, that could have been delivered by a team of 4 in 6 weeks for the price of a few pizzas. Nor do they seem terribly worried about the opportunity cost of having all those people duct-taped to their desks for all those months, busily waiting for each other to "review" or "approve" things.

I’ve been wondering, lately, why none of those people wants to shoot himself in the head.

I mean, the dysfunction is obvious. The remedies are simple and painless, really. Sure, we all talk about how hard it is to change, but isn’t it really just a question of seeing the value and making the choice? It’s sort of like choosing to stop poking yourself in the eye with a stick. The more I study the phenomenon, the less I understand it. Positive change makes things easier, not harder. Better ways of doing things also happen to be easier ways. Come to think of it, I guess that’s more-or-less axiomatic. So, "change is hard" doesn’t seem like a satisfactory explanation. It seems like a cop-out. Still, when I mention these things, I tend to get a lot of "What the hell is water?" reactions.

The only explanation I can come up with is that there must be something in the status quo that brings people value. Clearly, they aren’t getting what they need as human beings directly from their day jobs. Maybe they fear that if they were expected to invest more of themselves in their day jobs, they would have proportionally less to invest in the things that truly define them.

Very few people are defined by their day jobs. Maybe someone like Steve Jobs, who self-actualized through his company. But not many. For some of us, the day job is part and parcel of who we are. In my case, for instance, helping people discover their own strengths and find their own path toward professional growth (that’s what a coach does, by the way) is an important part of my personal journey of self-actualization. But it isn’t my biography; not by half. For most people in the IT field, their day job probably accounts for considerably less than half of what makes them who they are. For many, I suspect, it’s just a paycheck. "I’d rather be flying," as the bumper-sticker says.

So, maybe people figure out how to get what they need from their day jobs without burning themselves out to such an extent that they can’t continue to develop as humans after work. Maybe they apply their intelligence and creativity elsewhere, on their own terms, for their own purposes. It would sure explain a lot.

That notion made me wonder how much more effective organizations could be, and how much better our societies could be, if we aligned natural human values with the values on which our organizations and societies are based; if we could have organizations that treated people as, you know, people, instead of as "resources;" if we non-machines were no longer trapped in a machine, like so many mouthless Harlan Ellison characters.

I started to examine this idea by exploring the premise that our society’s values are the values of a machine, and yet we ourselves are not machines parts. The situation creates a conflict between the things we naturally want from life and the things our society expects us to want; the things our society demands that we want. We are required to want to live in service to the Machine. Yet, this is contrary to our human nature.

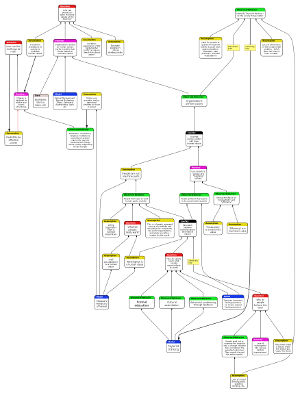

We are thus compelled to lead a double life; a life of deceit. One side of our split personality pretends to be a dutiful machine part with no independent desires or goals. The other side seeks out the things that will enable us to reach the highest level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Self-actualization. The crude beginnings of dot-connection activity are represented in the diagram below. No doubt it could stand some refinement. Feel free to offer suggestions.

[…] Fish gotta fly Written by: Dave Nicolette […]

Dave – I loved this blog so much! Thank-you for sharing it. I had a good look at the diagram and a few things stuck out to me:

1) I agree that critical thinking (or absence of) is a problem. But why is it absent? I think that thousands of years of behaviour, re-embedded by parenting and educational training skills has resulted in us not doing this anymore.

2) I agree that a large part of the problem may be that people don’t care and are just there for their pay packets… to some extent. When people join a new organisation they are passionate. They do care, they are re-ignited to make a difference. So what changes? They become embedded into the culture, the culture de-motivates them and then they stay there for the pay or until they wake up. Singular voices are repressed in organisations. As I like to put it “It’s all well and good to beat your head against a wall, but at some point in time you are going to get brain damage.”

3) Are there ways for voices to drive change to culture without being in management? I find often that people want to go into management mainly because the managers are doing such a terrible job at it. What if there was a way to be heard? I wonder whether it is critical thinking skills that are missing or if it is listening and action skills that are missing. In a world that is moving so fast these days we seem to shift and re-shape endlessly given what is happening around us but rarely over what is happening within. When we are fatigued over so much change is it any wonder that we don’t listen when those inside organisations beg for more change?

Hi Renee,

Thanks for the thoughtful comments and good insights. I don’t have the answers, but I’m interested in finding them.

I see the pattern you note regarding new employees quite often. In most client organizations I visit, the people who seem most interested in positive change are those who have been on staff for a year or less. Those who have been on staff for 2 to 5 years tend to say things like, “You can try to introduce change if you want, but you won’t get anywhere.” Those who have been on staff longer than that tend to be disengaged. Some may smile and shake their heads at the enthusiasm of the change agents. They have worked out how they can best survive and, maybe, get something they need on a human level after all, without fighting the machine.

Nice post. And a key question: “Why do people put up with it?”.

“The organizations snapped back to their old equilibrium state” minded my of the idea of Organizational Homeostasis (Sharon Drew Morgen, for one, explains this well in “Dirty Little Secrets”). Essentially, it’s the fear of a “mess” that holds people back from committing to change. I’m sure there are often other factors at play too, but Organizational Homeostasis is a bitch.

PS As I’m sure you know by now, the Marshall Model explains much in this regard, also.

– Bob

Hi Bob,

Clearly the Marshall Model has much to offer. I’ve added it to my collection of models.

As to the question of why people put up with it, I’m thinking that people aren’t actually putting up with anything; rather, they are actually getting something they need, on some level, from the status quo. If we could discern what that is and provide it in a more constructive way, we may be able to achieve genuine and lasting organizational improvement.

I’ll have to find “Dirty Little Secrets”. I haven’t read it. Sounds interesting. I’m not sure how people can be afraid of a mess when they’re already in one. That’s one reason I suspect they don’t feel as if anything is wrong; they must be getting something out of it. I wonder if they fear getting into a mess, or if they fear losing what they’ve managed to carve out for themselves under the radar.

Hi Dave,

Is the absence of something not of value in itself? For example, I value NOT having a hungry tiger in my living room.

Although, actually I do agree that it’s likely that folks are getting something – or more likely some things – from the status quo. I’m wondering what some of those things might be. Stable income might be one (although more likely a surrogate for other needs). I’ve long believed that self-image has a major role to play in motivating people (both for and against change), so that could be another.

Hope you enjoy the insights in the book.

– Cheers

I mean, the dysfunction is obvious. The remedies are simple and painless, really. Sure, we all talk about how hard it is to change, but isn’t it really just a question of seeing the value and making the choice? It’s sort of like choosing to stop poking yourself in the eye with a stick. The more I study the phenomenon, the less I understand it.

Some reading in psychology, cognitive dissonance, and behavioural economics might help.

Here’s something else—a macro expansion. Think of “obvious” as seven-letter replacement for “apparent to me”.

–Michael B.

Hi Michael,

Very good point. Yes, the dysfunction is apparent to me. I think it’s apparent to a lot of other people, too, but maybe not so much from the perspective of the fish who have always lived in the same water.

“Some” reading in [related subjects]…Well, I’ve tried that. I think the next step will have to be “a whole lot more” reading in those subjects. There has to be a reason behind these repeated behavior patterns, but it isn’t apparent to me.

It is widely documented that we physiologically fire the same neural pathways in circumstances that are familiar to us. We can generate new neural pathways but they don’t fire to be the normal behaviour straight away. It takes approximately eight months of constant repetition for the pathway to become a norm.

This is my understanding of neuroscience, limited given my reading.

The only explanation I can come up with is that there must be something in the status quo that brings people value. Clearly, they aren’t getting what they need as human beings directly from their day jobs. Maybe they fear that if they were expected to invest more of themselves in their day jobs, they would have proportionally less to invest in the things that truly define them.

That’s not my experience at all: I would love it if I could actually write good code at work – it feels like stealing when I work on hobby code at night, instead of interacting with my family.

But no, I waste eight hours each day trying to find and remove bugs from hideously bad legacy code acquired from other companies. I put up with it because my family needs my $80K paycheck and my medical benefits.

If I knew how to fly out of the stagnant water up to Agileheim, I would have done it a decade ago.

Hi Malapine,

I’m not sure we’re saying very different things. Let me see if I understand correctly.

I don’t want to reduce the world to a single model, but if you consider Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, your description fits.

“Write good code” is important to you. “Interact with family” is important to you.

You are getting value from your day job – money that you need to support your family. That is a basic human need. You are getting enough money from this job that you can afford to be concerned about higher-level needs, like “write good code.” That means your life is pretty good.

If writing “hobby” code is important enough that you sacrifice some of your family time to do it, then clearly writing good code is a significant part of your personal journey of self-actualization. You aren’t “stealing” anything when you do it, you’re pursuing your own fulfillment. This is not wrong. Each of your family members probably has hobbies, too. If you feel your time is not properly balanced, that’s a different issue.

It sounds as if you would like it if you could obtain some of that fulfillment at work.

You might be able to change your personal relationship to your work: Can you approach debugging the legacy code as a challenging sort of game? Are you familiar with “Forensic Development” (Llewellyn Falco & Jason Kerney)? How about the “Mikado Method” (Daniel Brolund & others)?

You might be able to influence change in your organization: Are you the only person who feels this way? You are aware of the water. What would it take to make key stakeholders/managers aware of it? If you are silently absorbing all the pain, what would signal management that anything is wrong? What would it take to generate critical mass to effect meaningful change?

You might be able to find a better place: In the US, the general unemployment rate is about 9%, but the rate for the IT sector is about 2%.

I think we’re actually saying the same thing, basically.

BTW, where’s Agileheim? Sounds like a Norwegian village where they train dogs for those agility competitions. Is it near Trondheim?

Hi Dave, thanks for your reply

I could treat debugging as a fun game, but if we go with Maslow, my problem isn’t boredom but fear: the codebase sucks, we have no idea whether the features are what customers want, and if the product doesn’t sell, some of us may get laid off. If that’s ever me, I am screwed: my resume will show two decades with the same employer, the vast majority of it on Waterfall or ScrumBut projects.

Off the job, I read books on Agile, go to monthly dojos, etc. ;but on the job I can’t even do TDD properly – builds take 20 minutes just to compile, and nobody else seems to care.

Agileheim is by analogy to Vanaheim (the mythical land of wise and productive gods). It’s at the opposite end of the world-tree from Taylorheim.